01/10/2019 | Category: Commercial Insurance

The motor trade industry consists of the entire infrastructure around all kinds of motor vehicles. It starts with their design, development, manufacturing and marketing, followed by their sale, maintenance and repair. It also includes the production, distribution and sale of components, spare parts and accessories.

As such, apart from the major car companies, the industry includes the support and collaboration of many commercial (and non-commercial) organisations. The British motor trade industry is a foundation of the wider economy and its performance has been a barometer of the state of the nation’s industries since its inception.

Any severe blows to the industry can, for example, affect employment in a particular region, while growth in vehicle sales has a positive knock-on effect in terms of new jobs created and prosperity through a high volume of work available.

Around 3,000 companies are involved in the motor trade industry, from manufacturers (mass-market and niche market) to suppliers to mechanics and garages around the country, servicing the multiple needs and desires of individual owners and commercial companies whose main activity involves vehicles.

The following history provides an overview of the British motor industry as a whole, looking at significant periods where changes and developments were to have a lasting impact.

The origins of the motor trade industry

The motor trade has its origins in the development and production of the petrol engine in the mid to late 19th Century in France and Germany. Britain joined the fray soon after and before long, there were hundreds of small companies producing hand-made cars for the wealthy.

Most of these small businesses didn’t last long, so the industry was left with around 100 companies who were able to make it to large-scale production. These companies had a significant history in the manufacture of moving vehicles (such as bicycles or horse-drawn trailers) or mechanical engineering, especially the production of heavy machinery. Examples of such companies were Germany’s Daimler and Wolsey and Lanchester in the UK.

Two notable exceptions to this rule were Ford in America and Rolls Royce in the UK. These companies drew on the engineering expertise developing in the industry and connected it with their business prowess in marketing and sales.

The 1920s onwards – mass-production

The motor retail trade industry was still in its infancy when the first industry body was established. This would ensure uniformly high standards in technical and production quality controls across the industry.

Known as The Institute of the Motor Industry, the organisation spread around the UK, holding meetings and conferences to discuss growth in the industry and exchange best practices. It soon grew to over 3,000 members.

However, when it came to large-scale production of specific models of vehicles, the Americans were at the forefront of the industry. They introduced the concept of mass-production – this process combined standardization, precision, interchangeability of components and synchronization of the multiple stages of the production process (by creating the assembly line).

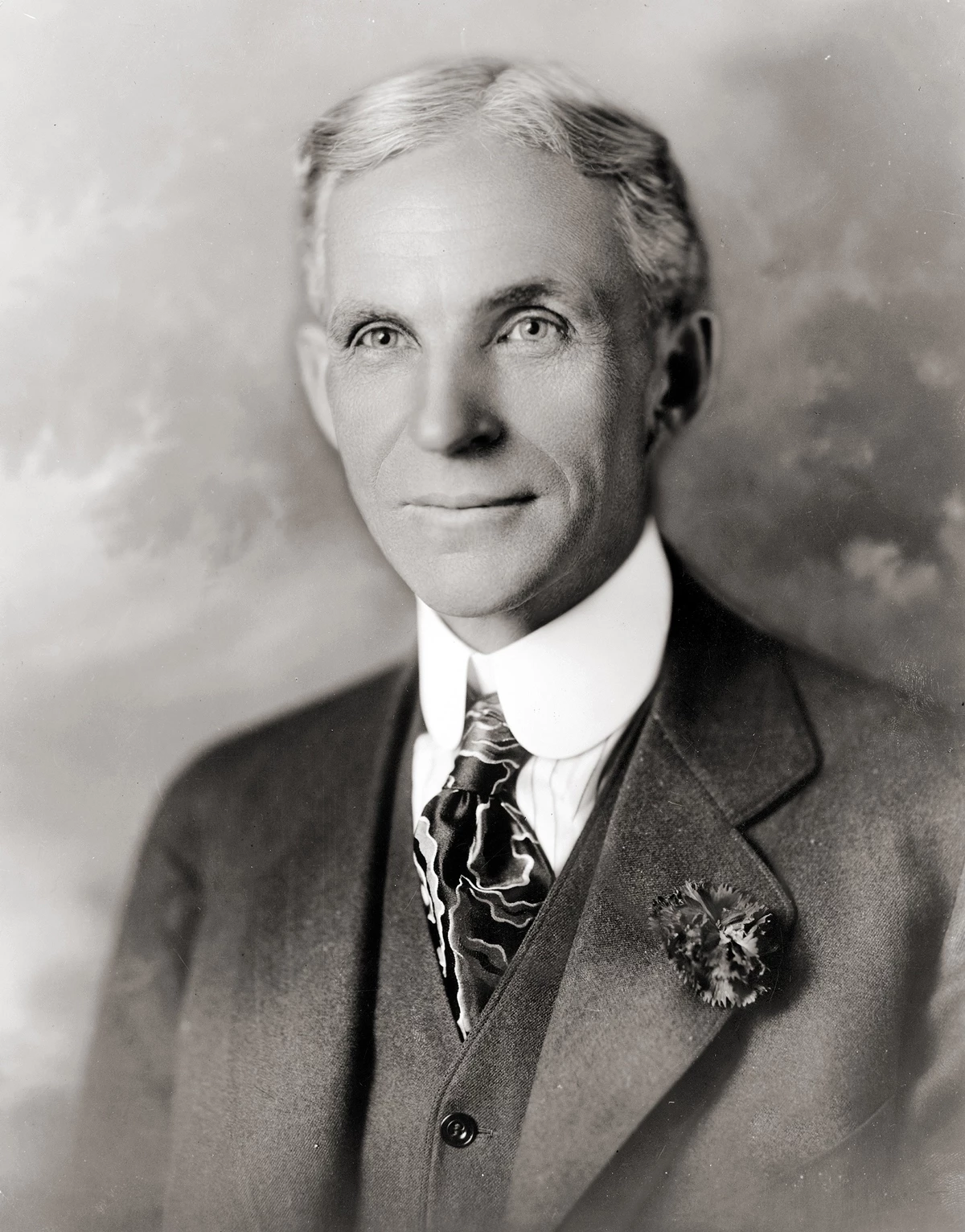

It was Henry Ford who kick-started large-scale production in the UK. He set up Ford’s first production plant in Manchester in 1913 and became the UK vehicle industry’s leading producer, followed by Wolsey, Humber, Rover and Sunbeam. These British companies had all been manufacturing cars since the turn of the century.

The great Wall Street crash had a serious impact on the world economy and the number of motor vehicle companies in the UK (previously around 200) fell back to around 50. Two familiar names, Morris and Austin were responsible for most of the car production in the years after the crash.

The 30s, World War Two and its aftermath

By 1939, British manufacturers (and European manufacturers in general) had adopted the same mass-production principles as the USA but the two markets were very different.

The UK was much smaller, its citizens had much less purchasing power and its tax and tariff policies made it more restrictive as a market.

Even so, the trend toward concentration of production in the hands of fewer companies was clear – between 1920 to 1930, the number of companies fell to 41, of which, three – Austin, Morris and Singer – had captured over 75% of the market.

Despite operating in a more limited market, the UK motor trade industry was expanding. In comparison to the more mature US market, companies were not competing for a smaller market share, so production growth continued in the 1930s.

By the end of the decade, as World War Two approached, six major British producers dominated the market – Morris, Austin, Rootes (Hillman and Humber), Standard, Vauxhall and Ford.

However, we shouldn’t forget that the roots of globalisation were emerging in other European countries, with the growth of giants like Volkswagen, Peugeot, Renault and Opel (actually owned by General Motors, whose acquisition policy had allowed them to make considerable inroads into European markets).

However, in general, the automotive industry saw a sharp rise in production in the years after the war, most of which happened outside the USA. UK vehicle exports reached unprecedented levels and, before long, Britain became the biggest exporter of motor vehicles in the world.

In 1950, 75% of car production and 60% of its commercial vehicle production meant it boasted 52% of the exported vehicles worldwide.

1950-1970 – mergers, acquisitions and refinements in production

Once the post-war situation had settled, the American owned companies in the UK (Ford and Vauxhall) held nearly 30% of the British market,more than either of the UK's top two British-owned companies. This was what drove the creation of the British Motor Corporation (BMC), whose aim was to dominate the British market.

Founded in 1952, it was made up of the big names in the British motor trade – Wolseley, Morris, Austin, Riley and MG. It soon captured the biggest single share of the British motor market. But overseas companies weren’t standing still during this period. German companies were rebuilding on the foundations of their unrivalled industrial capacity and steadily increasing their production capabilities. By the early 50s, German car production had overtaken France and was rapidly catching up with Britain.

There weren’t any major innovations over this period, rather, a trend of refining existing production techniques. Diesel engines were becoming popular for larger vehicles like trucks and buses, while automatic transmission became an attractive alternative for high-end car models. Aesthetics and comfort gained increasing importance for mass-produced models, with attractive and striking designs at every turn, alongside luxury features like air-conditioning.

By the mid-fifties, only five companies accounted for 90% of motor vehicle production, while the Rover, Jaguar and Rolls Royce brands had a strong presence in specialist luxury niches. However, there were clear problems associated with highly labour-intensive production methods and the unfeasibly large range of models offered by major British manufacturers. The unit costs in the British auto industry were unfavourable when compared to European, American and particularly Japanese competitors.

It was also becoming increasingly clear that the British economy was unhealthily dependent on the success of the motor trade industry. Foreign companies, particularly Ford, also had a strong foothold in the UK market, accounting for several thousand jobs at some of the biggest plants in Europe.

As a countermeasure, the British government pushed through a merger between Leyland-Triumph-Rover and the underperforming BMH, creating one of the largest car manufacturers in Europe. Known as the British Leyland Motor Corporation this new giant announced its investment in a new range of vehicles and refitting of its plants with the latest production facilities.

The 1970s – trials and tribulations

The 70s were to prove a turbulent time for the British motor trade industry due to a combination of factors.

The case of British Leyland

Despite having some notable models, British Leyland’s name has become etched in our collective memories of British industrial history as one of the greatest ever examples of company mismanagement, misfortune and misplacement of strategy. It had originally been touted as the ultimate British motor trade industry response to the threat of American and European domination. Its ultimate undoing was due to multiple factors;

· Internal management strife, causing a lack of clarity in strategic decisions on models, marketing and production. This included the production of models which were competing for the same market segments, essentially cannibalising each other’s sales.

· Unattractive models (the Austin Allegro springs to mind – it became notorious as an example of all that was wrong with British car-making).

· Production issues – inefficient deployment of new equipment and constant supply chain problems.

· Industrial disputes between management and unions – in fact, the UK car industry was only one victim of the 1970s era of nationwide unrest caused by industrial disputes.

In early 1975, the British Leyland Motor Corporation group closed down with debts calculated at some £200 million. The Government nationalised the company they had helped create only seven years before. They officially renamed it ‘British Leyland’.

The oil crisis

Another factor adding to the difficulties of the British motor trade industry in the 70s was the oil embargo. After the six-day war involving Israel and Arab states, Middle Eastern producers used an oil supply embargo as a way of putting pressure on Western countries, leading to petrol-rationing, serious transport difficulties and ultimately, a three-day week in the UK.

Fierce foreign policies

Foreign car companies had seen a steady rise in popularity in the UK market since the early 60s and by the start of the 70s, companies like Volkswagen, Renault and Peugeot had a strong foothold in the UK, to the extent that they were beginning to build production plants in Britain to manufacture right-hand drives aimed squarely at British drivers.

The Japanese weren’t missing a trick, either. Toyota, Nissan (under the Datsun brand name) and Mazda had already registered healthy sales and they would soon be joined by Honda (building on their success in the UK as a motorbike manufacturer).

The 80s to the noughties

By the end of the 1970s, there had been several major changes in the kinds of cars produced for the British market. Front-wheel drive had become a common feature, and the hatchback design was widely adopted.

After the troubles of the 70s, British workers were seen as being unproductive (thus, expensive) and prone to industrial strife. So, foreign manufacturers started moving their major production plants to mainland Europe (for example, Ford to Germany, Opel to Belgium and Spain), where labour costs were much lower. With unfortunate symmetry, British Leyland closed down its last overseas production plant in Europe at the start of the 80s.

By the early 80s, the Conservative government legislated to remove the power of the trade unions and continued to finance British Leyland, but actual production was reduced to two major plants – Longbridge near Birmingham and Cowley in Oxford. Many historic names in British car manufacturing disappeared. MG, Triumph, Morris and Austin all ceased functioning as brand names often subsumed under other, newer brand names for a more modern marketing approach.

Digitalisation and Brexit

Which brings us to today. The Society of Motor Manufacturers & Traders (SMMT) has been consistent in its message – an exit from the EU without any kind of trade deal would have a catastrophic impact on the UK motor vehicle sector, as it would signal an end to ‘frictionless’ trade with mainland Europe, adding massive amounts to the cost of importing and exporting.

This could seriously affect the security of thousands of jobs in an industry which contributes over £18 billion to the UK’s economy. The writing is already on the wall, as investment in new projects has fallen by 80% in the last three years, while car manufacturing in the UK has fallen by 9% in 2019.

The UK motor trade industry finds itself navigating turbulent seas today. A British-owned motor vehicle industry is a distant memory, while factories and plants located in the UK have largely become one small link in the global supply chain used by the multinational giants.

Nevertheless, there are still smaller online networking groups keeping the flame of traditional British motor trade burning.

Motor trade insurance – protection in stormy times

In terms of the motor trade industry as a whole, it’s worth diving deeper to get a holistic view of the state of the industry right now.

The British motor trade industry is looking to invest more in attracting and serving the needs of its customers using digital channels, according to industry experts.

This move online has impacted not only the way customers buy vehicles but also how they obtain insurance cover.

Insurance Choice should be your first port of call when looking for motor trade insurance.

Whether you’re a mechanic or a trader, you can simply enter some details on the website and one of our experienced team will call you back. We can arrange bespoke policies to suit any type of motor trade business, so why not give us a try?

Get a quote today.